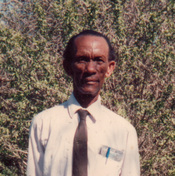

Paul Maignan Cemarc was a pillar in the community in which I minister. He was born in 1926, and began teaching school in this area back in 1949. He taught students for about 60 years of his life. He died in August of 2014.

I had the pleasure of working with Cemarc in the WFL school. In 2006 and 2007 we met every Wednesday. Cemarc would tell me stories about life as he remembered it in his early days. I would give him an assignment to write about another subject for the next week (holidays, jobs, experiences, games he remembered playing, hurricanes he remembered surviving, people he remembered...). He would come back with two pages typed on his manual typewriter. It was from those stories and documents that Cemarc and I created a book. The book (in Haitian Creole) tells the story of Cemarc's life and connects his life events to world events that are relevant to the folks here in Haiti. The name of the book is DIREK. A school principal here in Haiti is a director, and Haitians love to abbreviate titles to show affection. Cemarc was the beloved DIREK of many, many students.

Cemarc's birthdate is a date that recurs in Haitian history...April 21st. President Dumarsais Estime was born on that date in 1900 as was president Alexandre Boniface in the year 1934. April 21st is also the date that the Haitian government gave as the death of Francois Duvalier in 1971, though many people suspect his death may have taken place earlier.

April 21st 1926 is also the birthday of Queen Elizabeth, meaning Cemarc and Elizabeth were born on the very same day. One born into royalty in Europe, the other born into poverty on a Caribbean island.

Cemarc was blessed with a vivid memory. He would site for me a string of prices that he remembered from his father's time...a mule sold for 29 gourdes...a donkey for 18 gourdes. A few weeks later, with no prompting he would mention the same prices from the same time period. Cemarc vividly remembered walking behind his father when he was only a year old or so. His feet were suffering in the rocks and thorns of rural Haiti. He was complaining. Cemarc remembers his father turning around and picking him up. He also remembered that his father often had a piece of roasted potato in his pocket that he would share with Cemarc...his first child.

Everyone in Haiti knows the name Sylvio Cator. It's the name of 'the' soccer stadium in Port-au-Prince. Fewer people know why the stadium is named Sylvio Cator. Cator was a silver medalist in the long jump in the 1928 Olympic games. Cemarc was 2 when Cator jumped further than almost everyone on the planet.

When Cemarc was a toddler, his father Osias was not inclined to send him to school. It was a town authority named Vatel Bernadel who convinced Osias to send little Cemarc for a formal education. In October of 1929, little Cemarc heard the ringing of the school bell for the first time. He was a student. School for Cemarc was like coming home. Reading, writing, math and science were his friends. He would spend the rest of his life in schools.

In 1930, FIFA organized the first World Cup soccer tournament. It is a tournament that stops the world (and Haiti) in its tracks every four years. Cemarc was 4 when the World Cup began.

On the occasion of his first communion, Cemarc's parents bought for him a white hat. It was beautiful. Cemarc wore the hat to school for years. In the month of May, 1941, Cemarc remembers leaving the hat in school because it was a dreary, rainy afternoon. May is still the rainiest month of the year in Haiti. The next day, he returned to school, but the school yard was empty. He walked to the director's house. The director's wife made a joke about him never coming to visit them. The director appeared with the key and gave Cemarc the hat. Cemarc remembers asking why the school was empty. The director explained that the new president was taking the oath of office. The date was May 15, 1941. The president was Eli Lesko.

In 1947, the Haitian government established a testing site in Miragoane for primary school students. Cemarc, from Fond-des-blancs, had never had the chance to take his primary school exams. He was now over 20 years old. He had been studying regularly and had begun teaching younger students. But in 1947, he had the occasion to get his primary education certificate. It was a monumental task for a rural Haitian student.

Cemarc's family was not wealthy in any respect. He borrowed shoes to travel to Miragoane for the exam. The shoes were too small for his feet, and he remembers being in pain while taking the exams. It was a priest named Clervil who opened his heart and his pocket to help the young student Cemarc. Clervil helped cover the expenses of traveling to Miragoane for the exam. When Cemarc told the story to me, his eyes teared with love for the man who opened another door of education. Cemarc took the tests, passed, and received his primary school certificate. Cemarc brought me the original document so that we could make a copy for the book. It is dated 1947 and shows every sign of being that old.

Cemarc grew up in the mountain community of Fond-des-blancs. The teachers at the Catholic school were all from out of town. Cemarc was one of the first in Fonds-des-blancs to achieve his primary school certificate. Secondary education was next for those able to afford it. Cemarc’s family was once again unable to cover the costs of this next step in their son’s education.

In 1947, once again Father Clervil stepped in and made it possible for Cemarc to advance, attending secondary classes in the city of Miragoane. Father Clervil’s generosity left a mark not only on Cemarc Paul Maignan, but also on the community of Fond-des-blancs in general. A street sign there is labeled: J.J. Clervil. In Miragoane, Cemarc was once again discovering new things…Latin, English, Spanish, biology, and physics. He was in his element.

A case of malaria ended the school year early for him, and Cemarc ended up walking home from Miragoane to his father’s house in Fond-des-blancs. Weeks drifted by and Cemarc was unable to pay for his return to class. The candle of hope for continuing secondary school dwindled as each day passed.

During the post-war summer of 1948, Cemarc’s dream was to return to secondary school. But another major step in his life was around the corner. Father Clervil came to him this time with an offer. Would Cemarc, at age 22, be willing to direct a new school in the town of Labaleine? He had been teaching informally for years already, but now he chose to ‘become’ a teacher and director in one big step. After one month of work, Cemarc received his salary of $3. He went back to Fond-des-blancs and found Vatel Bernadel who had convinced Osias to choose the path of education for his oldest son. Cemarc shared his salary with Vatel saying, “The first harvest should be for the man who made it all possible.”

During the first year for his career, Cemarc bought material for a pair of pants. He paid twenty cents. Another 12 cents went to the tailor for sewing the pants, and Cemarc was dressed for work.

In 1949, Father Emile Roze decided to send Cemarc to the town of Laborieux, a fishing village on the southern coast to direct a school. Cemarc had lived in the mountains all of his life. Now he was on a plain next to the ocean teaching the people of Laborieux to read and write. He held the role of Director in that school for 35 years. He taught children and adults, and he taught the generations that came after them.

In the eighty’s, Cemarc left the Laborieux school to direct a brand new school in Pasbwadom. It wasn’t much of a school. In 1989 Water For Life began supporting that school. Cemarc, at age 63, humbly accepted the role of teacher. According to his account, the role of teacher ‘paid better’. The director had to make sure every teacher received money at the end of the month, and there was often precious little left for the director. As teacher, he received a regular salary.

As administrator of that school, I sat down with Cemarc in the 1990's when one of the the missions supporting the school began enforcing a rule that said all teachers must be Christians. It was a proper rule. Cemarc was Catholic, and in Haiti Catholic’s are not Christians in the eyes of many Protestants. We let Cemarc go, and he humbly accepted his fate.

He taught and directed at other schools off and on. In 2006 or so I invited him back to be our school’s historian. He met with me weekly until I was no longer the administrator of that school. Our meetings became less frequent. Last Spring I video-recorded Cemarc saying the name Asaph for the ASAPH Teaching Ministry video that is currently being made. He was wearing his ASAPH bracelet that I always saw on his wrist. In July I visited with him before flying home for a week. It was the last time that I saw him.

Cemarc typed these words in 2007 as the conclusion to the book he and I wrote together:

The title of teacher that I have today is a title that I’ve had since before I earned my primary school certificate. While I was a student, I formed an informal school in my hometown during vacations. I did that beginning in 4th grade. It was not the ‘fundamentals school’ program of today, it was traditional education (memorizing and reciting). I have fond memories of the little town where I grew up. My childhood was there. That’s where I lived, grew, learned to read, write and calculate. It’s where I ‘student taught’ during vacations (frankly, not ever knowing what was to come).

It was a beautiful life then, O Lord my God. It’s like I can see it now, though I am 81 years old. As I recall those days, I feel younger once again…like a boy of only 15. Thank you, Lord. I praise Your Name for that.

Children are the future of the country.

Take a good look at them.

You’ll see life in front of you.

Paul Maignan Cémarc

I had the pleasure of working with Cemarc in the WFL school. In 2006 and 2007 we met every Wednesday. Cemarc would tell me stories about life as he remembered it in his early days. I would give him an assignment to write about another subject for the next week (holidays, jobs, experiences, games he remembered playing, hurricanes he remembered surviving, people he remembered...). He would come back with two pages typed on his manual typewriter. It was from those stories and documents that Cemarc and I created a book. The book (in Haitian Creole) tells the story of Cemarc's life and connects his life events to world events that are relevant to the folks here in Haiti. The name of the book is DIREK. A school principal here in Haiti is a director, and Haitians love to abbreviate titles to show affection. Cemarc was the beloved DIREK of many, many students.

Cemarc's birthdate is a date that recurs in Haitian history...April 21st. President Dumarsais Estime was born on that date in 1900 as was president Alexandre Boniface in the year 1934. April 21st is also the date that the Haitian government gave as the death of Francois Duvalier in 1971, though many people suspect his death may have taken place earlier.

April 21st 1926 is also the birthday of Queen Elizabeth, meaning Cemarc and Elizabeth were born on the very same day. One born into royalty in Europe, the other born into poverty on a Caribbean island.

Cemarc was blessed with a vivid memory. He would site for me a string of prices that he remembered from his father's time...a mule sold for 29 gourdes...a donkey for 18 gourdes. A few weeks later, with no prompting he would mention the same prices from the same time period. Cemarc vividly remembered walking behind his father when he was only a year old or so. His feet were suffering in the rocks and thorns of rural Haiti. He was complaining. Cemarc remembers his father turning around and picking him up. He also remembered that his father often had a piece of roasted potato in his pocket that he would share with Cemarc...his first child.

Everyone in Haiti knows the name Sylvio Cator. It's the name of 'the' soccer stadium in Port-au-Prince. Fewer people know why the stadium is named Sylvio Cator. Cator was a silver medalist in the long jump in the 1928 Olympic games. Cemarc was 2 when Cator jumped further than almost everyone on the planet.

When Cemarc was a toddler, his father Osias was not inclined to send him to school. It was a town authority named Vatel Bernadel who convinced Osias to send little Cemarc for a formal education. In October of 1929, little Cemarc heard the ringing of the school bell for the first time. He was a student. School for Cemarc was like coming home. Reading, writing, math and science were his friends. He would spend the rest of his life in schools.

In 1930, FIFA organized the first World Cup soccer tournament. It is a tournament that stops the world (and Haiti) in its tracks every four years. Cemarc was 4 when the World Cup began.

On the occasion of his first communion, Cemarc's parents bought for him a white hat. It was beautiful. Cemarc wore the hat to school for years. In the month of May, 1941, Cemarc remembers leaving the hat in school because it was a dreary, rainy afternoon. May is still the rainiest month of the year in Haiti. The next day, he returned to school, but the school yard was empty. He walked to the director's house. The director's wife made a joke about him never coming to visit them. The director appeared with the key and gave Cemarc the hat. Cemarc remembers asking why the school was empty. The director explained that the new president was taking the oath of office. The date was May 15, 1941. The president was Eli Lesko.

In 1947, the Haitian government established a testing site in Miragoane for primary school students. Cemarc, from Fond-des-blancs, had never had the chance to take his primary school exams. He was now over 20 years old. He had been studying regularly and had begun teaching younger students. But in 1947, he had the occasion to get his primary education certificate. It was a monumental task for a rural Haitian student.

Cemarc's family was not wealthy in any respect. He borrowed shoes to travel to Miragoane for the exam. The shoes were too small for his feet, and he remembers being in pain while taking the exams. It was a priest named Clervil who opened his heart and his pocket to help the young student Cemarc. Clervil helped cover the expenses of traveling to Miragoane for the exam. When Cemarc told the story to me, his eyes teared with love for the man who opened another door of education. Cemarc took the tests, passed, and received his primary school certificate. Cemarc brought me the original document so that we could make a copy for the book. It is dated 1947 and shows every sign of being that old.

Cemarc grew up in the mountain community of Fond-des-blancs. The teachers at the Catholic school were all from out of town. Cemarc was one of the first in Fonds-des-blancs to achieve his primary school certificate. Secondary education was next for those able to afford it. Cemarc’s family was once again unable to cover the costs of this next step in their son’s education.

In 1947, once again Father Clervil stepped in and made it possible for Cemarc to advance, attending secondary classes in the city of Miragoane. Father Clervil’s generosity left a mark not only on Cemarc Paul Maignan, but also on the community of Fond-des-blancs in general. A street sign there is labeled: J.J. Clervil. In Miragoane, Cemarc was once again discovering new things…Latin, English, Spanish, biology, and physics. He was in his element.

A case of malaria ended the school year early for him, and Cemarc ended up walking home from Miragoane to his father’s house in Fond-des-blancs. Weeks drifted by and Cemarc was unable to pay for his return to class. The candle of hope for continuing secondary school dwindled as each day passed.

During the post-war summer of 1948, Cemarc’s dream was to return to secondary school. But another major step in his life was around the corner. Father Clervil came to him this time with an offer. Would Cemarc, at age 22, be willing to direct a new school in the town of Labaleine? He had been teaching informally for years already, but now he chose to ‘become’ a teacher and director in one big step. After one month of work, Cemarc received his salary of $3. He went back to Fond-des-blancs and found Vatel Bernadel who had convinced Osias to choose the path of education for his oldest son. Cemarc shared his salary with Vatel saying, “The first harvest should be for the man who made it all possible.”

During the first year for his career, Cemarc bought material for a pair of pants. He paid twenty cents. Another 12 cents went to the tailor for sewing the pants, and Cemarc was dressed for work.

In 1949, Father Emile Roze decided to send Cemarc to the town of Laborieux, a fishing village on the southern coast to direct a school. Cemarc had lived in the mountains all of his life. Now he was on a plain next to the ocean teaching the people of Laborieux to read and write. He held the role of Director in that school for 35 years. He taught children and adults, and he taught the generations that came after them.

In the eighty’s, Cemarc left the Laborieux school to direct a brand new school in Pasbwadom. It wasn’t much of a school. In 1989 Water For Life began supporting that school. Cemarc, at age 63, humbly accepted the role of teacher. According to his account, the role of teacher ‘paid better’. The director had to make sure every teacher received money at the end of the month, and there was often precious little left for the director. As teacher, he received a regular salary.

As administrator of that school, I sat down with Cemarc in the 1990's when one of the the missions supporting the school began enforcing a rule that said all teachers must be Christians. It was a proper rule. Cemarc was Catholic, and in Haiti Catholic’s are not Christians in the eyes of many Protestants. We let Cemarc go, and he humbly accepted his fate.

He taught and directed at other schools off and on. In 2006 or so I invited him back to be our school’s historian. He met with me weekly until I was no longer the administrator of that school. Our meetings became less frequent. Last Spring I video-recorded Cemarc saying the name Asaph for the ASAPH Teaching Ministry video that is currently being made. He was wearing his ASAPH bracelet that I always saw on his wrist. In July I visited with him before flying home for a week. It was the last time that I saw him.

Cemarc typed these words in 2007 as the conclusion to the book he and I wrote together:

The title of teacher that I have today is a title that I’ve had since before I earned my primary school certificate. While I was a student, I formed an informal school in my hometown during vacations. I did that beginning in 4th grade. It was not the ‘fundamentals school’ program of today, it was traditional education (memorizing and reciting). I have fond memories of the little town where I grew up. My childhood was there. That’s where I lived, grew, learned to read, write and calculate. It’s where I ‘student taught’ during vacations (frankly, not ever knowing what was to come).

It was a beautiful life then, O Lord my God. It’s like I can see it now, though I am 81 years old. As I recall those days, I feel younger once again…like a boy of only 15. Thank you, Lord. I praise Your Name for that.

Children are the future of the country.

Take a good look at them.

You’ll see life in front of you.

Paul Maignan Cémarc